Re-living May Day 1971 on My 45th Sober Anniversary

The best part about being clean & sober is being able to remember what I did yesterday and not be ashamed. The best part of being clean and sober for 45 years is knowing that I didn’t get this far alone and that sometimes looking at the past through a new pair of glasses might illuminate nooks and crannies of morality left unseen.

Today, I feel “less than” very acutely. I feel ashamed and powerless as a once-proud American watching what is being done to trans folks, to people of color, to women, to immigrants – to us LGBTQ+ folks, the pariahs, the ignored, forgotten ones - like kidnapped and imprisoned gay Venezuelan stylist Andry Hernandez Romero – and so many others, the ones too afraid to attend Pride parades or go to work or see their doctors.

I have been heartened, however, by the protests – from a handful of local folks with signs standing alongside a road to the 4-6 million who participated in the #NOKings protests around the country.

The First Amendment right to speak freely, to experiment with self-expression and freedom of association, to protest oppression and what I believe is wrong is fundamental to American democracy. And that means the person I disagree with has a right to speak out, too, without demanding their citizenship papers.

This has been a lifelong evolution.

As a teenager enthralled with JFK and the civil rights movement, I increasingly defied my military family to participate in Students against the Vietnam War. Those were MY friends being drafted.

Some of my friends fled to Canada; some sucked ink through punctured Bic pens to screw up Xrays during their physicals; some pretended to be homosexual without realizing the implications. This was a time when it was not OK for men to hug other men so I watched on the tarmac as friends would shake hands before one headed off to war.

It was all so unfair. I felt so powerless, drinking myself into oblivion when my friends came home in body bags or missing a limb or their sanity.

We were the little nameless ones for whom the war was just wrong. But together, we had hope. We made up signs and slogans like “Make Love, Not War” and we sang about the “Age of Aquarius” and flocked to the Woodstock Music Festival for a shot of communal joy.

Stoned and sharing doobies with my activist brothers and sisters, I helped take over our college administrator’s office. I got pelted with eggs and tomatoes by the “Love it or Leave it” hard hats loyal to the war effort.

But it was May Day 1971 that made me realize that I might be more than a face prepared to meet the faces that I meet, to crib from T.S. Elliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

My friends and I arrived in Washington DC in a VW van on Friday night, May 1, from upstate New York. Our first stop was the White House where we all got out and loudly sang “Find the Cost of Freedom” into the dark night. We set up with everyone else in West Potomac Park. We were nervous. The violence at the 1968 Democratic Convention and Kent State were top of mind. No one cared when protesters yelled, “The Whole World Is Watching!”

Attorney General John Mitchell had issued a “martial law” order and Washington DC was under curfew and siege. According to the ACLU, over 5,000 armed cops, military police, a helicopter battalion and 1,400 National Guard were on duty and visible on every block.

The two male Maoist leaders of our little eight-person group were really pissed off. Unbeknownst to me, one of them brought a gun and the other had several baseball bats. They wanted to sneak out after dark and create havoc.

I freaked out. I didn’t care who they were – I didn’t sign up for this, I yelled. The others ran over to see what was happening. Each of us had our say and then insisted we take a vote. “All those who DO NOT want to take a gun and baseball bats and create havoc – raise your hands.” Even the in-charge Maoists respected that the majority voted with me to be non-violent.

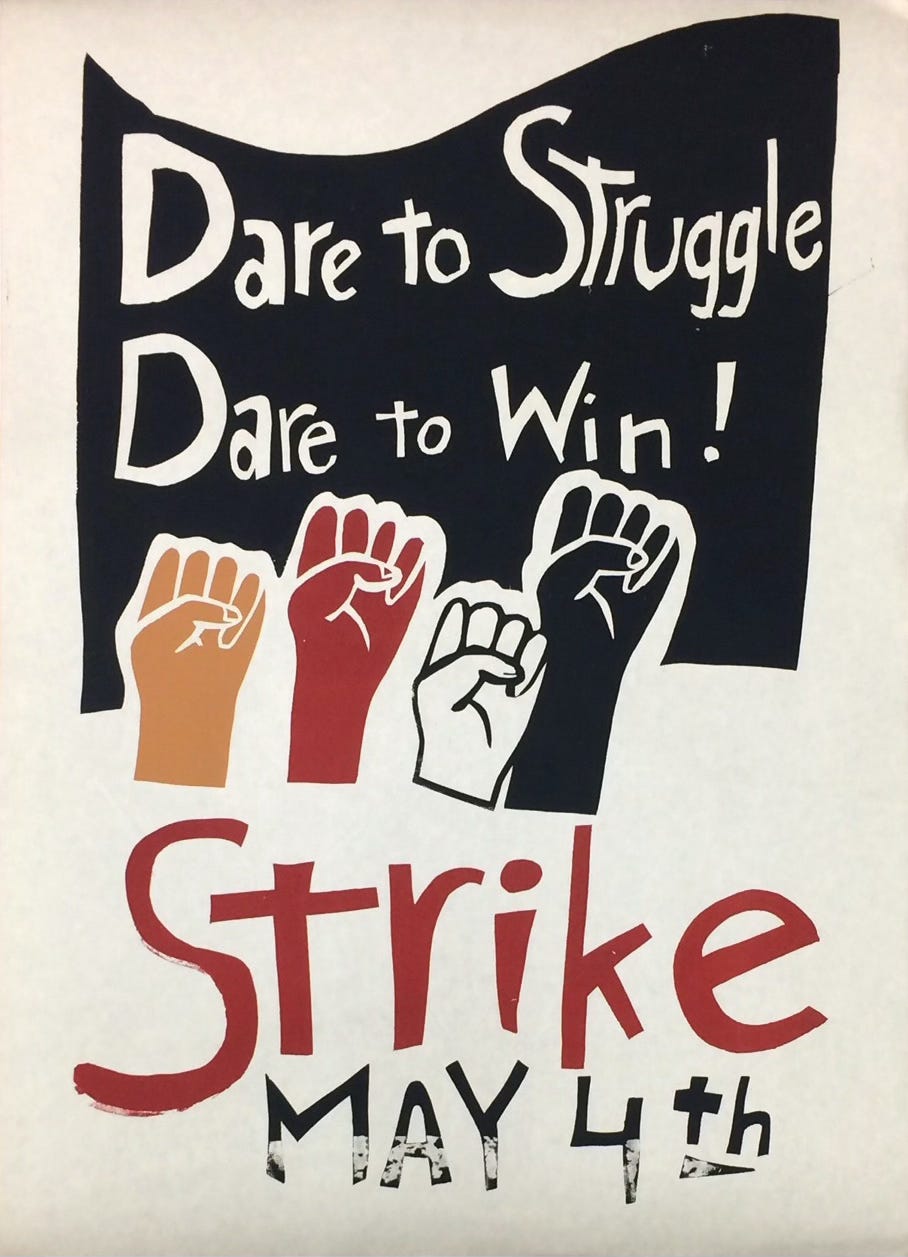

The next day, we were all pushed out of West Potomac Park. We went to Georgetown University campus, which was cool since our May 3 Mayday assignment was the nearby Key Bridge. Our slogan was: "If the government won't stop the war, we'll stop the government.”

That Sunday afternoon, as I’m standing on the chow line on the athletic field, a line of men wearing tutus and veils pranced by. They twirled a bit then disappeared.

Who are they? I asked a guy in line. “They’re gays.” I recoiled and stared. I’d seen homosexuals in Greenwich Village – effeminate men and butch women. But they were different from the women I slept with during my shameful “sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll” days. The guy told me about the Stonewall Riots and Gay Liberation – dousing me with truth and history, awakening my sleeping soul.

But with the gays flitty disappearance, we shifted to Kent State. Just a year earlier, on May 4, 1970, twenty-eight Ohio National Guard soldiers shot 67 rounds over 13 seconds into a crowd of hundreds of unarmed college students, killing four and wounding nine others protesting Nixon’s expanding the Vietnam war into Cambodia. Time magazine later wrote that "triggers were not pulled accidentally at Kent State."

College campuses erupted in protest. Then ten days after Kent State, on May 14, 1970, students at the historically Black Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi were protesting the Kent State massacre and ongoing racial harassment when two students were killed and 12 wounded by police.

One account reported: “There was screaming and cries of terror and pain mingled with the noise of sustained gunfire as the students struggled en masse to get through glass double doors. A few students were trampled. Others, struck by buckshot pellets or bullets, fell only to be dragged inside or left moaning in the grass.”

Roughly one year later, on May 3, 1971, we girded ourselves for this new kind of civil war. Cops had no problem shooting or beating a person to death to protect a piece of property. When we were pushed back and fled, we were chased by men with outstretched guns.

The war had come home.

Eventually, we wound up back on the athletic field of Georgetown University. We were surrounded by police who used Billy clubs, tear gas and pepper spray to disperse us – with nowhere to go. Police helicopters swirled overhead, dropping gas canisters into a growing dense cloud of gas spreading over the field.

From behind my LSD eyes and foggy gas mask, I could see a young man in the middle of the cloud, picking up hot canisters with his bare hands and lobbing them back at police. Finally, he collapsed. I tried to get help but the world had gone mad, people running, getting arrested, sitting with their bleeding heads in their hands, trying not to pass out.

It was up to me. I made sure I had my wine and water pouches and cloth for his eyes and I ran into the cloud. He was on the ground, too weak to move. I got his arm around my neck and dragged him out to the makeshift first aid area. I washed his eyes and face and told him how brave he was. Somehow, we both managed to escape arrest. According to the ACLU, over 7,000 people were arrested that day, the largest in US history.

The next day, we marched through the DC streets with mini rallies here and there with more than 12,000 more arrested.

As I passed by the Treasury Department, I saw the guy I helped hanging with several of the gay men I’d seen prancing around two days before. This time I was sober so I recognized that I was drawn to them, though I didn’t know why.

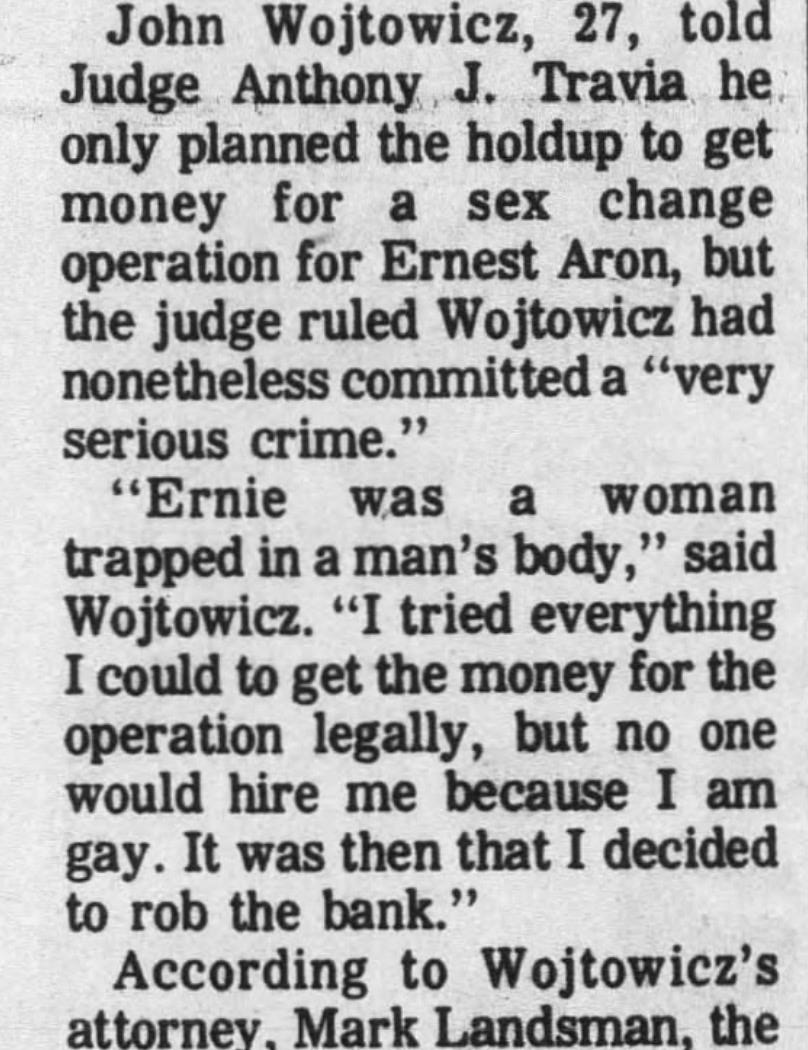

Decades later, for some reason I told this story at a gay 12 Step meeting in West Hollywood. A man approached me afterwards and said the person I rescued was Ernest Aron, the gay man for whom John Wojtowicz tried to rob a bank to get money for Ernie’s sex change operation. The story was captured in the movie “Dog Day Afternoon.”

May Day and this subsequent awareness reemerged as I watched news accounts of masked, unidentified ICE and border agents with the California National Guard snatching people up based on racial profiling and disappearing them. The Trump administration is enforcing Project 2025, which calls for the absolute erasure of LGBTQ+ people. But, as this May Day story illustrates, we’re tougher than we look, tougher than they think we are and some of us are going to enjoy wearing tutus even under the threat of armed cops.

I may feel ashamed today for being so powerless in the face of our crumbling democracy. But May Day gives me hope that even if I can’t be strong enough – at least I can share stories about those who are. Thank you, sobriety!